|

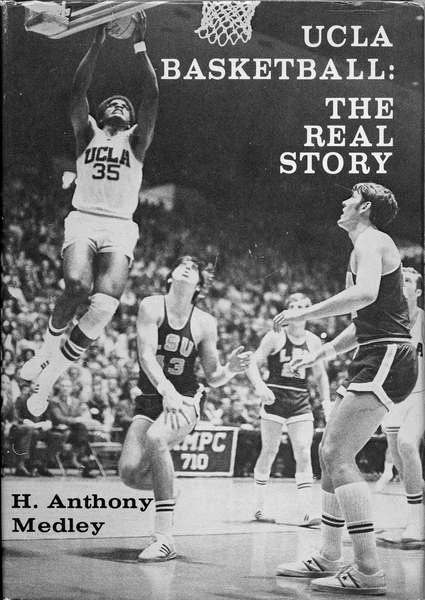

Out of print for more than 30 years, now available for the first time as an eBook, this is the controversial story of John Wooden's first 25 years and first 8 NCAA Championships as UCLA Head Basketball Coach. Notre Dame Coach Digger Phelps said, "I used this book as an inspiration for the biggest win of my career when we ended UCLA's all-time 88-game winning streak in 1974." Compiled with more than 40 hours of interviews with Coach Wooden, learn about the man behind the coach. Click the Book to read the players telling their stories in their own words. This is the book that UCLA Athletic Director J.D. Morgan tried to ban. Click the book to read the first chapter and for ordering information. |

|

One-on-One with Wes Parker by Tony Medley I was at an evening game in 1970 at Dodger Stadium between the Dodgers and Cincinnati. Late in the game the Reds brought in a 19-year-old rookie lefthander named Don Gullet. He proceeded to mow the Dodgers down with a fastball that looked faster than Bob Feller. Aspirins would have been easier to hit. Up strode Dodger Wes Parker. Until 1970, Parker had been known as a fancy-fielding, light-hitting first baseman. But in 1970 he blossomed, ending at .319 for the year. This night, with Gullet throwing bullets, Parker worked the count to 3-1. Then Gullet threw a fastball across the heart of the plate and Parker swung easily, knocking Gullet’s fastball into the left field pavilion. I reminded him of this home run when we met at The Beach Club in Santa Monica. “You were there that night?” he asked. “I guessed fastball at 3-1 and was right. That was a real important home run for me because I was having my best year and approaching 100 RBI. I don’t remember it because it was off Gullet. I remember it because of how important it was to my RBI total.” I asked him how he turned from the hitter with a .245 lifetime batting average in the spring of 1969 into the guy who hit .319 with 111 RBI in 1970. He said, “In the spring of 1969, Al Campanis had only recently been named General Manager of the Dodgers and he was sitting on the bench during spring training talking with Tommy Lasorda, who was then a coach to Manager Walt Alston. He told Tommy that I’d never be a great hitter. Tommy jumped up and said, ‘I can make him into a great hitter.’ You know how Tommy is. Campanis was dubious, but told him to go ahead. “So Tommy worked with me diligently. We worked early, way before game time, and then after the game. He’d pitch to me and keep telling me that I was going to be a great hitter. The first two weeks I thought he was crazy, blowing smoke. But he kept at it, kept repeating what a great hitter I was going to be. Sometime during the third week I began to believe him. “Then the next spring (former Dodger great) Dixie Walker came to camp and worked with me. He told me I was uppercutting the ball and if I could cure that, I’d be a much better hitter. I told him I knew that but I didn’t know how to stop it. So he worked with me like Tommy had and finally, after hours and days and weeks of practice, I was able to change my swing so that I didn’t uppercut. The results were amazing.” That’s for sure. In 1968, Parker had hit .238. After Lasorda’s tutelage, his average improved to .278 in 1969. Then after Walker worked with him, his average climbed to .319 in 1970 with 196 hits. His last two years his average plummeted to .274 and .279, not bad, but not .319. I asked him what changed. He revealed, “Being a great hitter required so much effort I didn’t enjoy baseball any more. I worked so hard that year, and it required me to put so much concentration into the game that it was pure work. I wasn’t a natural hitter; it came hard for me. I had to think about baseball all day long. Then I had to get off by myself 20 minutes before each game to quiet down my mind. I had to stop doing clinics and guest appearances. There was no more of going to dinners and banquets. I could do no socializing. Just to maintain my focus I had to immerse myself in baseball to keep my mind totally involved, to the total exclusion of everything else, like enjoying life. Sure, that was my best year at the plate. But it was also the most unenjoyable year I had in major league baseball. “That off season I said to myself that this game should be fun like it used to be, so I’m going back to enjoying myself. I still had good seasons the next two years. From ‘69 on I was an excellent clutch hitter. I adopted the attitude that it was not how many hits you get; it’s when you get your hits. My concentration was there when it needed to be, when the game was on the line and runners on base. But I couldn’t grind out the hits the way I did in 1970.” Then at the peak of his career, when he as only 32, he quit. Why? “Three reasons:

“Campanis and Peter O’Malley tried to talk me out of it. ‘We need you,’ they said, ‘to help with our transition with younger players. You have at least 5 more good years.’ “I said, ‘No, this is the right time. I’ve thought about it and this is the right time’.” I asked him what it was like playing behind the legendary Sandy Koufax. “Playing behind Sandy was a great privilege. It was absolutely different from playing behind anyone else. Watching Sandy pitch was a little bit like watching God. Everybody felt like that. “Sandy was quiet, reserved, standoffish. He was popular because of his talent, not because of his personality, but he was a good guy. People respected him. He was not a leader, except by example. Contrasted with Sandy, Don Drysdale was through and through 100% a leader. Don had a great personality. He was outgoing, a terrific teammate. With Don, it was all about winning and unselfishness. He was a terrific storyteller.” Parker attended high school at Harvard school in the Valley, where he played baseball. He attended Claremont College, where he played baseball and was quarterback on the football team for one year. He gave up football because his father advised him if he got hurt it could jeopardize any career he might want in baseball. Because of a family situation, he transferred to USC and graduated from there. “I hadn’t thought about baseball as a career until then. I had worked out with the Dodgers when I was in high school. Charlie Dressen (who had managed the Dodgers to two pennants and a tie between 1951-53, when he quit because Walter O’Malley wouldn’t give him more than a one year contract) was a coach, had seen me play American Legion, and invited me to Dodger Stadium. I went as often as I could. “(Then Dodger first baseman) Gil Hodges was a very nice man and very helpful. He told me how to play first base. At the time I did it like everyone else did it then, switching my feet on the bag depending on where the throw was. “Gil told me that was wrong. He said if I was left-handed, I should always touch the base with my left foot. He showed me how it was so much better, and that’s the way I’ve done it ever since. “He also told me that I should be smooth. While that might have helped me, too, because I know I was always smooth, I think that’s something you’re born with. “After I graduated from SC I called Charlie and begged him to sign me, which he did. I played one year in the minor leagues and was always over .300, so the Dodgers brought me up.” What Hodges told him obviously worked out well, because Parker was just named the best fielding first baseman in baseball history by Rawlings, who took a nationwide poll to pick the all time best fielding team. Garnering 53% of the votes cast for first basemen, Parker not only got more votes than all the other first basemen combined, he got more votes than anyone on the team, including Willie Mays! After leaving the Dodgers, Parker played in Japan for a year, was a TV commentator for several years for the USA Network, became an actor and did lots of commercials. Then he took a job with the Dodgers as a speaker, which he still does today. In addition, he donates one day a week working for the Braille Institute. “I talk to them about sports, about whatever sport is in season at the time,” he says. He is still in shape, at 6-1 with a 33-inch waist. He also plays golf and bridge. In fact, he is one of my bridge partners. I thought I was overly competitive until I played with Wes. If what I am is competitive, there’s a higher word for what Wes Parker is. |

|

|