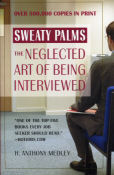

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. Click the book to order. Now also available on Kindle. | |

|

Patrick Wayne Reflects on John Wayne as a Father by Tony Medley Although John Wayne is one of Hollywood’s larger-than-life stars, to my sister, Melinda, and me he was the father of our schoolmates, Patrick for me and Toni for my sister. One of my sister’s earliest memories occurred when she was at Toni’s house and John walked in. Toni said, “Daddy, I want you to meet my friend, Melinda.” My sister, remembers, “It’s such a vivid memory. I was only about seven and he wasn’t close to the megastar he became. It was a couple of years after Stagecoach (1939). I’m not sure I knew who he was, although I knew that Toni’s father was an actor in the movies. I remember how big he was, just huge. He asked me if I wanted some ice cream and I said yes. He asked what flavor and I said vanilla because I couldn’t think of anything else, so he made me an ice cream cone. I just remember how sweet he was, even kind of shy, nothing like you think of when you think of a movie star, and how nice he was to me, just a little girl. My husband says that I’m probably the only person in the world for whom John Wayne made an ice cream cone.” As for me, I still remember when Patrick was absent from the fourth grade when his father took all four children to Ireland for the filming of The Quiet Man (1952). I reminded Patrick of this when we met at Chez Nous restaurant in Toluca Lake. Patrick told me, “That was my first exposure to acting. Dad asked if we wanted to be in the film, and, since it gave us something to do while we were on the set, and we were there for six weeks, we all agreed. As I got older and working on other projects I decided that’s the career I wanted to follow.” Looking fit and trim at 6-1, 195 pounds, I asked him if his father wanted him or any of his siblings to work in the industry. Patrick said, “He never encouraged us to do anything. His attitude was, ‘Your life is yours to live and you have to figure out what will make you happy.’ He was happy and proud when I decided to pursue a career. After I got out of school I told him that I wanted to become an actor. Up to that time when I was in school I worked every year acting. I did lots of films, like The Long Gray Line (1955) and The Searchers (1956). C. B. Whitney was the producer of The Searchers, and he put me under contract. Dad was my agent and he insisted that they pay me all year round, but that I only work during the summertime. He didn’t want my education being disrupted.” Even though Patrick was only four years old when his parents divorced, he said he spent as much time with his father as if they had still been married because John was on location so much. “Because I was working in the industry I got to spend more time with him than my brothers and sisters. He came over for birthdays and we would drive over to see him when he was in town. It was fun. He’d have films for us to see, like Laurel and Hardy. I asked him if and how his father influenced his career. He answered, “Most of what I learned from him I learned by example. He was a pro through and through. He always showed up on the set ready with dialogue. But more important he was prepared for the skills he had to use. For example, in Hondo (1953) he had a real long monologue that he had to give while he was working like a blacksmith shoeing a horse. He originally didn’t know anything about blacksmithing. So he would arrive very early on the set. While they were setting up the sets, getting the lights and everything, he was working on how to do the task of blacksmith work. He spent hours practicing what he had to do so that when the scene was shot he wouldn’t have to think about the task he was doing, blacksmith work, while he was speaking his lines. Because of all his practice with the blacksmithing, doing the work was second nature to him by the time of the filming of the scene. This enabled him to concentrate on the dialogue. That’s what people don’t even think about. If the physical thing went wrong, something would be wrong with the scene because it would be apparent that he didn’t know what he was doing.” In responding to my question whether or not he was hard to please, Patrick said, “He wasn’t critical, but he took pains to make sure that I knew what I was doing so I didn’t look bad. In The Commancheros I was riding a horse in a running insert, a very critical shot. As the scene was shot, I looked awful. It looked like I didn’t know what I was doing riding the horse. He came to me and said, ‘You’re going to learn how to ride a horse,’ and he made sure I learned. There was a later scene when I looked very good, so good that they reshot the earlier scene so that I looked as good then as I did later in the film. “I really took that to heart. When I was filming Sinbad, I auditioned for the role in a fencing scene with a stuntman. They liked it and hired me to star in the film. ‘We start in a month,’ they said. Remembering how conscientious my Dad was in learning tasks, I told them I wanted to work with a stuntman to learn about fencing, because I knew nothing about it. They said that we were starting in a month and they’d have a stuntman for me to work with in Malta. I refused, saying that I wanted to learn in the month before filming started. I said I won’t go unless I can work with him. So I worked everyday with him. When film started in Spain, before we got to Malta, the biggest sword fighting scene was filmed. Had I waited, that scene wouldn’t have been nearly as effective because I wouldn’t have known what I was doing. That was a film where there were lots of special effects. I was fighting monsters, but I was all alone with the monsters being put in later. They had budgeted two days for the sword fighting scenes, but I had learned the craft so well that we shot it in half a day. As a postscript, typically for Hollywood, instead of giving me the credit for insisting that I learn the fencing before production started, the producer came up to me and told me how smart he had been to insist that I learn the fencing before we started the shoot. I asked how his father behaved on the set. Patrick said, “Because Dad was such a star, he would get upset if something went wrong with a scene. He might explode, but if he did he would cool down and go back and apologize just as loud as he had been when he exploded, in front of everyone. He wasn’t afraid to express what he wanted. But there were certain directors, like Henry Hathaway, Otto Preminger, John Farrow, and John Ford, who were the bosses, even though he was such a star. Even with other directors, though, he respected them. “He was a terrific horseman. In Big Jake (1971) there is a scene at the beginning when the characters are introduced. Chris Mitchum rides a motorcycle into the scene and Dad is on a horse and it rears up and throws him. Later in film there is a chase and as they are passing by a bar a guy gets thrown out into street. Dad is riding a horse and the horse gets spooked and goes sideways. Dad stayed with it and stayed in the saddle, even though it was going sideways for ten feet, just an amazing display of horsemanship. It was all caught on film, but it had to be cut because it was inconsistent with the opening scene. A guy who could ride like that could never be thrown like he was thrown in the opening scene. “He was very athletic, a big, massive guy, but he was quick like a cat. When my sister, Melinda, got married, she and her husband, Greg were standing with the priest and the wedding party at the Communion rail. I was in the wedding party and Dad was sitting in the first row. I saw Melinda start to waiver, start to faint. As I moved to help her, Dad streaked by me and caught her. He was 32 years older than I, but I’ve never seen anybody move faster.” Then Patrick told me something that I don’t believe many people know about his father’s death. “Although Dad wasn’t religious, and not Catholic (we were raised in the Catholic faith by my mother, Josie), he used to say if he was anything he was a presbygoddamterian. By the time he was dying in the hospital, he still hadn’t been baptized. He was in a coma for his last ten days. I would go and sit and talk with him, even though he was in a coma. The Saturday night, two days before he passed away, he came out of the coma and my brother, Michael, Toni, and half sister, Aissa were there. He was awake for 2 hours, talking and responding, and then went back to sleep. We thought he was indestructible. On Monday, I was there and he was slowly getting worse and worse. The phone rings and it was the Catholic chaplain who wanted to come by. Even though Dad was still in his coma, I said , ‘Dad the chaplain wants to see you,’ expecting no response. I started to leave the room when I heard him say, ‘OK.’ I was stunned, but I called the chaplain, who showed up in 40 minutes. With him still in a coma. I said, ‘Dad, the chaplain is here,’ and, once again, he said, ‘OK.’ I left them alone for 15 minutes and could hear them talking. When the chaplain came out he told me he had baptized Dad.” Patrick’s parents had been divorced for the entire time I have known him. I had assumed that there must be some animosity between John’s old and new families. Patrick demurs,“I am very close to my half-siblings, especially Ethan and Aissa. In fact, Aissa is the family member I’m closest to. We were always close and mixed together. When Dad started his new family we embraced them. They got to know my mother and they loved her, and she embraced them. “We’re doing a lot of things together for the Centennial . Batjac was my brother Michael’s production company. Michael died of complications caused by lupus after surgery for diverticulitis. When he passed away, we formed a limited partnership to take care of the Wayne enterprise, and voted for a new general partner, Ethan, who runs the partnership. “I am Chairman of the Board of the John Wayne Cancer Institute. We raise money for Cancer research. Last April Ethan and I had an Odyssey Ball and the Wayne family donated $1 million. There are seven members in the Wayne enterprise, represented by each of Dad’s children. The interests of Toni and Michael, both of whom have passed away, are represented by Toni’s children and Michael’s widow, Gretchen. The family runs the entire operation. Ethan, as General Partner, makes all decisions. Ethan is 45, and worked as actor and stunt man and then with Michael running the business. Dad bought 600 acres in Sequim Washington on the Olympic peninsula, and we are now developing it. The state built a marina and we have all the property around it.. Ethan is running the entire operation.” To celebrate the Centennial of John Wayne’s birth on May 22, 2007, Paramount Home Entertainment & Warner Home Video will pool their DVD sales and marketing resources, digging into their vast libraries for a total of 48 popular Wayne classics. The lead titles in the promotion are Rio Bravo, in both a Two-Disc Special Edition, which includes extras like a documentary on Howard Hawks, among other extras, and Ultimate Collectors Edition, The Cowboys as a Deluxe Edition, and True Grit as a Special Collector’s Edition, both of which also contain extras.

|

|

|

|

|