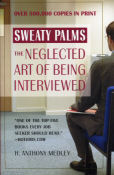

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. Click the book to order. Now also available on Kindle. | |

|

The Burial (3/10) by Tony Medley 126 minutes. R. At first glance, this is a pleasing, feel-good story about Jerry O’Keefe (Tommy Lee Jones) a white man, who sues Raymond Loewen (Bill Camp), a bad man billionaire who ran a huge company with 15,000 employees and operated 1,115 funeral homes, for breach of contract for $5 million. Jerry then replaces his white attorney with charismatic black PI lawyer Willie Gary (Jamie Foxx) who immediately ups the claim to $100 million. The point of the movie seems to be that this dispute between two white men is resolved by two black attorneys opposing one another in front of a black judge and a predominantly black jury in Mississippi. The only card Gary has to play is the race card and he plays it constantly. While it labors along for more than two hours and reaches its surprising conclusion that allows everyone to leave the theater feeling good, there were things about the film that deeply troubled me. Directed by Maggie Betts from a script by Doug Wright and Betts, based on a New Yorker article by Jonathan Harr, it also includes a “story by” credit to Doug Wright. That’s the big key. Why does a true story need a “story by” credit if it is telling it like it was? I knew nothing about this case so had to investigate it because what is on the screen is so bizarre from a legal point of view it seemed as if something was missing. What I found was astonishing. One of the many things about the film is that the black judge admits “evidence” that has no relevance to a breach of contract litigation. You don’t need to be a lawyer to have this slap you in the face. If you have only watched episodes of “Law and Order,” it will surprise you when you see some of the things that are allowed into testimony in front of a predominantly black jury. Spoiler alert: What is egregious about this film, though, is that the actual case is a textbook example of the unfairness of the American legal system. I can find no evidence that Loewen, who had acquired funeral homes all over the country, was running a corrupt organization, although one of my friends had experience with Loewen and advises that in his opinion he was not a good person (using a descriptive word not appropriate for this review). Here is one example he gives: Our chairman was visiting him re merger and other industry topics on Ray’s boat in Vancouver. Heated discussions ensued and my chairman asked to be returned to shore. Ray refused and continued confrontational comments. My Chairman, a good old Boy Texan, said if you don’t take me to shore I will throw your a** off this boat. The boat returned to shore. He was an a**h*** to his people also. I was not aware that he was corrupt, or cheated people. His organization was a formidable competitor in the acquisition arena. We competed to buy on many operations in No America. Disgruntled employees of his came to us and the same with ours went to him. But regardless of Loewen’s character, it is the actions that are meaningful and the final award was so outrageously inequitable, it should never have been allowed to stand. But because Mississippi law required anyone appealing a judgment to post a bond equal to 125% of the award, Loewen (and virtually nobody) could afford that kind of money to file an appeal. Nobody doubts that the original award was 20 times what could have been the actual damages, and the film does not make clear how punitive damages could be awarded for a breach of contract cause of action. That would only be appropriate if the cause of action included fraud and I don’t remember anything like that in the film. I asked the people who repped the film if the producers had any justification for this and they failed to provide one. A film about this case would have been more appropriate had the story been told from the POV of how Loewen and his company were destroyed by a flawed system of civil justice and a clever, devious attorney. But that would have made co-producer Foxx unable to make Gary look like a hero. This case has been widely criticized, but you’d never know it from this film that whitewashes a case that should be known for its notoriety, not praised. Postscript: Professor Sir Robert Jennings, Q.C, was asked to write an opinion of the case. Here are some excerpts from his 22-page opinion: My name is Sir Robert Jennings, Q.C. I am Emeritus Whewell Professor of International Law at the University of Cambridge, England. I am a former Judge and President of the International Court of Justice at the Hague. I am also a former President of the lnstitut de Droit International. In 1993, I received the Manley Hudson Gold Medal from the American Society of International Law. I am asked by Messrs Jones, Day, Reavis and Pogue, of Washington D.C. for my opinion in the case of The Loewen Group, Inc. (a Canadian corporation), and Loewen Group International, Inc. (The Loewen Group‘s United States subsidiary corporation) (the two are collectively henceforward “Loewen”), and on their prospects concerning a reparation claim against the United States, under the NAFTA treaty, arising from the proceedings brought against them in a Mississippi State Court by Mr. J. O’Keefe and a number of other associated plaintiffs. … It makes no difference that the manifest injustice in this case results from the verdict of a common law jury (a majority verdict of 11 votes out the twelve). (Tr. at 5732-33, 5811-12) it is clear that in the present case the origin of the manifest injustice was in effect created by a gross abuse of the system by plaintiffs’ leading counsel, which if not quite aided and abetted by presiding Judge, was at least tolerated and totally uncontrolled by the Judge, even though he knew very well the game that was being played in his court. There were so many occasions when the Judge ought to have stopped plaintiffs’ counsel; and occasions when he certainly ought to have warned the jury against counsel’s methods. Whatever the reasons for the Judge’s silences, and some of his curious utterances, the result was a remarkable travesty of justice. Moreover, the Judge’s observation that counsel was playing the “race card,” shows that the Judge was wholly aware of what was happening in his court. (Tr. at 359597) There are cases where bias, though wrongful, is relatively innocent because it is of the kind stemming from ignorance. This case was different. The jury might have been to some extent unaware of how they were being manipulated. But so far as the court was concerned, both the Judge and counsel knew perfectly well that counsel was intentionally stirring up racial and nationalistic bias against Canada and Canadians; possibly one must suppose because he had decided that this was the way he might win the case and harvest absurdly and outrageously inflated damages. He also intentionally befuddled the members of the jury with large sums, changing sometimes in a sentence from millions into billions, and adding words to the effect that “these people” spend this sort of money in an afternoon. It was a remarkable but most unsavoury performance. But the most telling aspect of this case is not the way the jury’s verdicts were brought about but the verdicts themselves. The sums awarded were so bizarrely disproportionate as almost to defy belief. To begin with, the sum of 100 million dollars “compensatory” damages awarded in a relatively straightforward and routine breach of contract case, that on the face of it involved at the outside, and assuming a finding wholly for the plaintiff, certainly no more than a few million dollars, and probably significantly less, was in itself massively disproportionate. Having decided that sum, the jury then went on to assess punitive damages at 160 million dollars. The second phase allowed counsel to mesmerize the jury into changing their own already grossly exaggerated sum of $160 million punitive damages into $500 million. In terms of denial of justice these astonishing figures speak for themselves. These verdicts were brought about by carefully calculated, and wholly improper means. The gross denial of justice was the intended result. … Professor Jennings’ entire scathing 22 page report may be read here: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0971.pdf

|

|

|

|

|