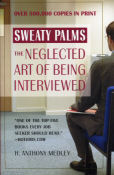

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. Click the book to order. Now also available on Kindle. | |

|

Trumbo (1/10) by Tony Medley Runtime 148 minutes including credits OK for children. In fact, this boring whitewash is probably real good for small children because it will put them to sleep almost immediately. A more sanctimonious film that takes itself so seriously you will rarely see. In fact there’s a line that Dalton Trumbo (Bryan Cranston) utters near the beginning of the film that aptly describes the movie. He talks of “days of lovely boredom.” The loveliness of the film is mostly in a few performances, namely Helen Mirren as Hedda Hopper, David James Elliott as John Wayne (even though Wayne is portrayed venomously, because he courageously stood up for his patriotic values and those are values disdained by the Hollywood left; still, Elliott captures his gait and way of speaking extremely well), and Dean O’Gorman as Kirk Douglas, who was, to put it charitably, a useful fool for the Hollywood Soviets in his support of Trumbo. They not only look like the people they play, they affect accents that are remarkably similar without being laughable Rich Little-like impersonations. On the downside, Micael Stuhlbarg’s performance as Edward G. Robinson falls far short of the mark. The only thing he captures of Robinson is that he’s short (5-4 ½). This was accomplished by utilizing camera angles, though, and through no effort by Stuhlbarg because he is 5-8. But what this does, is try to canonize Trumbo without evidence of any miracles. True to Hollywood’s political slant, they ignore the main problem with the Hollywood Ten, of which Trumbo was a charter member: why they were castigated. And the reason they were treated the way they were is that they all dedicated themselves to Soviet communism, pledging allegiance to Joseph Stalin, the biggest mass murderer in the history of the world, the man who murdered 35 million kulaks by starving them, his own citizens, to death. They all actively pursued their Communist ideology and filled their films with Communist propaganda, and Trumbo was a leader in this regard. There’s no mention in the film of Trumbo writing, “Every screen writer worth his salt wages the battle in his own way—a kind of literary guerilla warfare.” According to Kenneth Lloyd Billingsley in “Hollywood Party,” “Paul Jarrico (one of the Hollywood Ten) bragged that the (Communist) Party smuggled its ideology into all sorts of movies, claiming that the line he gave Burgess Meredith in Tom, Dick, and Harry, ‘I don’t believe in every man for himself. I get lonesome,’ became the battle cry of the Chinese Red Army." There’s no mention that Trumbo was an active participant in the public humiliation of Party member Albert Maltz, a prominent and successful screenwriter, who had the temerity to criticize the Communists’ use of art as a weapon in a February, 1946 issue of New Masses. All the Stalinists, including Trumbo, ganged up on him and made him participate in a private verbal flagellation followed up by a Soviet-style public recantation. Actress Carin Kinzel Burrows, who was there, described what happened, “Mr. Maltz got up and made a speech and said how wrong he had been, and blamed himself for having fallen into such a grave error and said art was a weapon and had to be used as a weapon. He publicly degraded and humiliated himself. It was a terrible spectacle to see a man I had always respected behave in this way.” There’s much more of what Trumbo and his Hollywood Ten comrades did that this movie totally ignores. They were a lot more than just pro-union activists, which is all this movie shows them to be. They were just as disloyal to America as Alger Hiss and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. I write this so if you do decide to go see this tedious, slanted film, you will know much more about Trumbo and his comrades than today’s Hollywood wants you to know. The most interesting part of the film occurs under the closing credits when photographs and film clips of the real people are shown. But it’s not worth waiting two hours that seem more like eight just to see them.

|

|

|

|

|