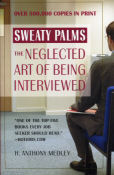

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

| Sequestro (8/10) by Tony Medley Run time 94 minutes. OK for children. According to this film, when the cold war ended the former Soviet Union stopped funding leftist movements. So the “Departamento América” assembled a group dedicated to commit kidnappings, heists, and bombings to raise money to finance Latin-American Guerrillas. In 1986 there were four kidnappings in Brazil; in 1989, there were eight. In the case of the kidnapping of Abilio Diniz, 5 Chileans, 2 Argentines, 2 Canadians, and 1 Brazilian were arrested and imprisoned, all members of MIR, Chile’s Revolutionary Movement. By 1992, there were 10 kidnappings and the kidnapping industry had generated over $10 million. In 1994 there were 15 kidnappings. In 2001 the kidnappings skyrocketed to 362. During four years, a film crew followed the classified investigations and tactics of the São Paulo Anti-Kidnapping Police Division. During that time, 376 people were kidnapped in the State, over 1,500 in Brazil. Written, produced and directed by Jorge W. Atalla, the film is dedicated to “people who, even being victims of one of the most cruel crimes committed, had the courage to give their testimony to alert society of the need to protect itself and fight for all its causes.” The cameras show the horror of kidnapping much better than a scripted show like Law and Order. They capture the tension and terror of confrontations between the kidnapper and the victim’s family. They show victims’ families talking to the kidnappers over taped telephone conversations, showing the brutality of the kidnappers. Shown with hand-held cameras are actual videos of the police tracking down the criminals, their strategizing, the advice they give the victims’ families, and the actual captures of several of the kidnappers. The film also includes interviews with captured kidnappers, who dispassionately adopt the guise of simple, gentle people working for a political belief. They show no appreciation for the horror they cause. They are true sociopaths, belying their avuncular images. Their victims include young children under seven years of age, one beautiful young woman, and an elderly man who was deprived of the more than 10 pills a day he required to keep healthy, and they were all treated without the slightest compassion. As Anderson “Andinho”, who spent 22 days in captivity, says, “No matter what I tell you about my 22 days they’ll be just words. You have to live it to understand.” Many of the victims are interviewed and tell in detail of their ordeals and how they were treated personally. Their stories draw a stark dichotomy between their horrors and the calm, dispassionate defenses given by jailed kidnappers. Then there are the videos of the victims’ families being pressured to pay the money demanded. Again, you dichotomize between the bland statements of the kidnappers interviewed earlier in the film, who clearly don’t care about the anguish they caused and the brutality of these conversations. The film closes with the police tracking down one of the victims. The cameras follow close behind and capture the moment he’s found. You won’t soon forget the looks on his face. First, the look of someone captured without hope, then the realization that it is over, the relief and the tears. Among the film’s final words are the kidnappee talking to his father on the telephone moments after his discovery and release crying into the phone with unabashed joy, “I love you. Dad, they found me!” In Portuguese. September 7, 2010

|

|

|

|

|