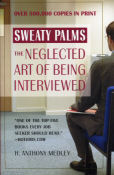

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

| Buzz (8/10) by Tony Medley There have been many stories told of Hollywood, most by actors and directors. A few writers have told what it’s like in modern day Hollywood, but I can’t think of a writer from the Golden Era of the ‘40s and ‘50s who has told the story. That’s what Albert “Buzz” Bezzerides does here. This is not only his story, but it’s him telling it. Never heard of Buzz? You aren’t alone. Have you heard of noir? Buzz is generally credited with having written the story which some claim to be the first American noir, “They Ride By Night” (1940) adapted from his novel “Long Haul.” And that story, which doesn’t come until well into the film, more about that later, comes with another story. Buzz wrote the novel (at the urging of his wife, Yvonne), and made around $500 on it. An agent came to him and said he could get him more money from Warner Bros., who wanted to make a movie out of it. The agent got him $1,500, and Warner Bros. signed him to a contract. On his first day at the studio he was in the office of the producer, Mark Hellinger, he saw Hellinger stick a script in the drawer. Buzz asked to see it and it turned out it was a complete script based on his book. They had been working on the script before they got the rights to the book. He had already signed a contract with Jack Warner for seven years, which Warner offered to avoid a lawsuit, paying him $300 per week, “but that was a lot of money for me.” Buzz said he could have gotten much more for it because he had them over the barrel. They had already started on the movie and didn’t have the rights. He said he was sold down the river by the agent who traded his obligation to Buzz for better continued relations with the studio. He said someone found a letter in the file saying they should pay him $20,000, but he said it didn’t bother him too much because that “would have spoiled me. I wasn’t writing for money; I was writing to write.” This was the first of deals where Buzz felt he was “swindled,” which he said continued throughout his career. This is only one of the many stories told in this fascinating study of a man who could be an icon but who is known only by the most devoted of movie fans. During his career, great actors came to him to polish their dialogue. Humphrey Bogart was the first, in “They Drive by Night” (the script was credited to Jerry Wald and Richard Macaulay), to ask Buzz to improve his dialogue. He liked what Buzz did so well that he continued to ask Buzz to do uncredited work throughout his career and recommended him to others who did the same. Eventually people like Edward G. Robinson and George Raft paid him as much as $5,000 to polish their dialogue. For a man given lots of credit for creating noir in the United States, Buzz’s life imitated his art. To hear him tell it, his career was just one swindle after another. Nobody ever treated him fairly, and he remembers and tells about each in detail. One interesting aspect of this film is that it shows trailers used to promote these films in the ‘40s. They are so far superior to the trailers of today that it bears commenting. In the ‘40s the trailers were teases, showing short clips but mostly voice-overs telling a bare outline of a plot. Trailers today not only tell almost the entire story, they show all the great lines. Once you’ve seen a trailer today there’s not much need to see the movie, and when you do see it, the trailer has spoiled the suspense and spontaneity. The film has its weaknesses. Among them, it’s too long at 118 minutes and it spends far too much time on Buzz’s upbringing, not getting into his Hollywood years until about 45 minutes in. I would start the film with some Hollywood reminiscences and then have a flashback to tell about how he got to Hollywood, and I’d only spend not more than 15 minutes on his upbringing and education. While his hardscrabble upbringing is slightly interesting, it’s what happened in Hollywood that makes this an entertainment worth watching. Another weakness is the story Buzz tells about how Ronald Reagan switched from being a member of the democrat part to the republican party, which sounds like sheer fantasy to me. In fact, Reagan was a member of the democrat party long after the anecdote Buzz relates allegedly took place. If the rest of Buzz’s remembrances are as accurate as this story, maybe this film is more fiction than fact. He tells of his left-leaning political views and touches on the Hollywood (or Unfriendly) Ten and the McCarthy era, which apparently affected his career. He had a dispute with John Howard Lawson, one of the more notorious of the Unfriendly Ten, over “Action in the North Atlantic,” (1943), which Lawson wrote. Although this movie doesn’t mention it, Lawson was such a Communist zealot that he said, “As for myself, I do not hesitate to say that it is my aim to present the Communist position, and to do so in the most specific manner.” Buzz spent so much time polishing “Action in the North Atlantic” he wanted a credit, which Lawson refused to share. He took Lawson to the Screen Writers Guild, which was dominated by Lawson’s Communist comrades, and lost. Another interesting aspect of the film is how he came to be William Faulkner’s savior while the Nobel- and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist was in Hollywood during World War II. Jack Warner was paying the world famous Faulkner $250 a week when Buzz was being paid $1,200 per week. There is very little narration. Most of the story is told by Buzz himself with personal remembrances voiced by Director Jules Dassin (“very few screenwriters are remembered, very unfair”), and actresses Cloris Leachman, Gloria Stuart (“he wasn’t an artist; he was an engineer. He always wanted to fix scripts”), and Terry Moore, among a few others Coming out of a screening for “Juke Girl” (1942), a crippled lady said, “Whoever wrote this sure knew his folks.” And it made Buzz feel great. Jack Warner didn’t hear it because he had left, saying, “I don’t know why everyone likes this picture.” But Buzz says nobody wrote realistic pictures. Buzz states a truth that many writers will recognize, that you don’t just work 9-5 and go home. “You work on it day and night. Sometimes you work on it in your dream and wake up with a solution.” Despite his constant carping about being victimized by so many swindles (“The world stinks because the men in it stink; they’re pigs”), he admits that “money didn’t solve my emotional problems. Writing did.” I’ve just scratched the surface. Even though it’s too long and needs editing, for anyone interested in Hollywood folklore this is a must-see.

|

|

|

|

|