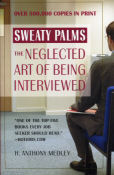

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

|

good night, and good luck. (8/10) by Tony Medley President Truman said that Senator Joseph McCarthy, the junior Senator from Wisconsin, was “the greatest asset that the Kremlin has.” Agreeing with Truman were many anti-communist Hollywood liberals like Ronald Reagan, Hollywood labor leaders Roy Brewer and Howard Costigan, and Sidney Hook, a Marxist scholar who turned against the Communist Party. Although there was a lot of fire in McCarthy’s smoke (one of his main claims, which is the prologue for this movie, was that there were “200 card-carrying Communists” in the State Department. Release of FBI files relating to the Verona Project after the fall of the Soviet Union pretty conclusively confirmed that Alger Hiss, a high-ranking State Department official, was a Communist traitor in spite of 40 years of denials by the left, so the State Department was Communist-infiltrated, as McCarthy alleged, although he later reduced the number), his tactics were those of a police state. Even so, using this quote of McCarthy’s as the prologue for the movie discredits the movie because it leads the audience to believe that the basis for McCarthy’s anti-communism was false, when it was clearly not false. It wasn’t McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade that brought him down, it was his tactics. For the record, there were communists in the United States, in Hollywood, and in the State Department. They were actively supporting Joseph Stalin, who is still the greatest mass-murderer in history. During the ‘30s he killed the Russian kulaks, its entire middle class, 50 million people, by starving them to death. There is nothing admirable or heroic about any of these American Communists. They were despicable people supporting a despicable monster. As to the notorious Hollywood Ten, sometimes referred to as the Unfriendly Ten (because they refused to name the names of their fellow Communists before the House Un-American Activities Committee, the alter ego for the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, of which McCarthy was Chairman), legendary director Billy Wilder said, “Two were talented, the other eight were just unfriendly.” Even so, the Hollywood Ten who took their marching orders from Stalin have been elevated to secular sainthood by the Hollywood left, who are the people making this movie. In 1954 McCarthy’s reign was attacked by a newsman, Edward R. Murrow, and it was the beginning of the end for Joe. This is a well-crafted, if sometimes draggy, documentary-style film about that attack. It is shot in black and white for a couple of reasons. First is that it adds to the verisimilitude of the story. The second is that the producers, rather than hiring someone to portray McCarthy, wanted to use Tail Gunner Joe uttering his own words, so they used old black and white news footage. Cutting back and forth between color and black and white to show McCarthy speaking would have interfered with the apparent currency of the film. David Strathairm gives an Oscar-worthy performance as Murrow. If you never saw Murrow, what you see in Strathairm will give you a good feeling for what you missed. Writer-Director George Clooney plays Fred Friendly who was the co-producer, along with Murrow, of Murrow’s show, “See It Now” (1951-57). Frank Langella gives a brilliant performance as William Paley, the autocratic head of CBS, who backed Murrow’s attack, even though it threatened the viability of his network. At one point in the film it is alleged that Paley said that McCarthy wanted William F. Buckley, Jr. to do his rebuttal to Murrow’s attack. Buckley graduated from Yale in 1950. He didn’t found “National Review” until 1955, one year after the McCarthy-Murrow dispute. I remember attending some of Buckley’s debates when I was at the University of Virginia Law School in the early ’60s. But I questioned whether he had the cachet in 1954, at the age of 29, to be considered as someone who could take on a national monument like Murrow on behalf of the most powerful man in the United States Senate. This is a strange, one line, insertion in the film that seems out of place with no apparent raison d’être. So I checked with Bill Buckley himself and he confirmed it, but he added something the filmmakers conveniently omitted. While McCarthy did ask him to do the rebuttal, and he agreed, when the McCarthy people submitted the request to Murrow, it was flatly rejected. Apparently Murrow wanted McCarthy to hang himself and knew that Buckley would be too formidable an adversary to achieve Murrow’s desired end. Clooney obviously didn’t want to reveal Murrow’s fear of Buckley, since the point of the film is to parade Murrow being steadfastedly brave. How would it look to have Clooney's valiant 50-year-old hero appear as a quivering lump of jelly, cowering in a corner hiding from an erudite 29-year-old? Even so, this is an entertaining, behind-the-scenes docudrama about how one man propelled television into a powerful presence in its infancy. If you didn’t live through these times, this movie does a good job of recreating them. September 8, 2005 |

|

|

|

|