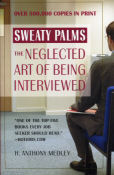

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

|

The Legend of Zorro (8/10) by Tony Medley Zorro’s back! Once again as Don Alejandro de la Vega, he is inhabiting the body of Antonio Banderas. He’s married to Elena (Catherine Zeta-Jones), who has become a female Zorro, at least as far as the fighting goes. They have a 10-year-old son, Joaquin (Adrian Alonso). Joaquin doesn’t know Don Alejandro is Zorro, or anything but a ninny who won’t stand up for his rights. There are two terrific bad guys. One is a French aristocrat, Armand (Rufus Sewell). The other is Jacob McGivens (Nick Chinlund). Armand is good-looking, suave, sophisticated, always with a knowing smile on his face, charming to the end. On the other hand, Chinlund is ugly, scarred, mean, and evil, not a good bone in his body. Even though it’s over two hours long, it bristles with uptempo adventure. In fact the only thing that slows it down are the silly fight scenes that are so long that they threaten to break the tempo that director Martin Campbell has brilliantly maintained after a long opening sequence that is far too ludicrous, so silly that it almost lost me at the outset. Also marring the film are some gargantuan historical fallacies. It’s set in 1850, the year California became the 31st state in the Union. Despite this, one of the bad guys is a confederate officer. Sorry, but the Confederacy wasn’t organized until 11 years later, right after Abraham Lincoln became President in 1861. Two men appear who identify themselves as “Pinkerton” men, working for the United States government. Alan Pinkerton, America’s first private eye, didn’t start his business until 1850, the year this film takes place. It was a private firm, not affiliated with the government. At one point Elena is dining with Armand in his mansion and she asks to go to the bathroom. He tells her it’s “down the hall.” While the first indoor bathroom was written about in 1840, it was a luxury for at least the next 20 years. It’s hard to believe that a wild place like pre-statehood California would have an indoor bathroom in 1850. The final part of the film takes place on a train. The building of the transcontinental railroad was authorized by the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, 12 years after the setting for this film. It was completed at Promontory Point, Utah in 1869, seven years later. A train wasn’t even a gleam in Californian’s eye in 1850. Even those these gaffes don’t upset the enjoyment of the film, filmmakers more sensitive to accuracy could have made a movie without these mistakes that wouldn’t have affected the film one iota, but would have had the advantage of being historically accurate. Regardless, this is a funny, action-packed movie. While Banderas and Zeta-Jones are first rate, the surprise of the movie is Alonso, who plays their spirited son, Joaquin, who has clearly inherited Zorro’s personality and fighting ability. For one so young, Alonso has exceptional talent. He adds immeasurably to the enjoyment of the film. A young boy being as good a fighter could have been ludicrous, but Alonso’s talent makes his ability believable without being too precocious. Even though it’s over two hours, the only times I got restless were when Zorro got in his ridiculous fights against overwhelming odds. Sink those and it’s a much better movie. Even with them it’s a lot of fun. October 26, 2005 |

|

|

|

|