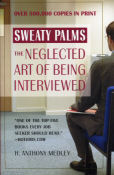

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

|

The Constant Gardener (7/10) by Tony Medley Justin Quayle (Ralph Fiennes) is a mild-mannered British diplomat who falls in love with the fiery, driven Tessa (Rachel Weisz) and marries her. At the beginning of the film, Tessa gets on a plane with her black friend/colleague, Arnold Bluhm (Hubert Koundé) and they end up murdered, Arnold brutally. Justin spends the rest of the film investigating her death. Although 129 minutes seems much too long, director Fernando Mierelles (“City of God,” 2002) takes a well-written script by Jeffrey Caine, from a novel by John Le Carré, and keeps the story moving at a reasonable pace. I read Le Carré’s first two books, “Call for the Dead” (1961) and “A Murder of Quality” (1962), and liked them both. They were clever little mysteries set in England that only sold a few thousand copies. Then he wrote “The Spy Who Came in From the Cold” (1963), which came out small like the first two, but was quickly grabbed by a major publisher looking for something to compete with Ian Fleming’s James Bond series. Given a huge promotion budget of $2 million (that’s in 1964!), it became a historical bestseller. However, good as it was, that was the end of the line for me. I tried to read his next few books, but, now that he was commercial, his writing changed and I found his subsequent work wordy and uninvolving, so gave up on him. He wrote “The Constant Gardener” in 2002. The character Tessa is based on a real person, Yvette Pierpaoli, who was apparently a dedicated woman, an activist who devoted her life to helping poor Africans. She died with two colleagues in an automobile wreck in Kenya in 1999 at age 60. Le Carré met her in the ‘70s. The film is an interesting thriller. Justin is in jeopardy throughout the entire film, but it doesn’t dissuade him from proceeding. One thing he is investigating is that the pharmaceutical company, with the help of the British and Kenyan governments, is testing an anti-TB drug, Dypraxa, on unsuspecting Africans. Tessa knew about it and was vocal in her opposition. Along the way he discovers other things that bother him about Tessa. His investigations run him afoul of the British establishment, including his friend Sandy Woodrow (Danny Houston) and Sir Bernard Pellegrin (Bill Nighy) of the British High Commission. Although his role is small, Nighy gives a terrific performance and has the funniest line in the film. Devoid of special effects, despite some terrific and beautiful African locations, this is a film that is script-driven. The premise is that pharmaceutical companies maximize profit at the expense of public welfare. Although I know big business is rife with corruption, this contains some key scenes that are based on a counter factual premise. Near the climax, Justin finally comes in contact with Lorbeer (Pete Postlethwaite), a doctor, for whom he had been searching throughout the film. Lorbeer is outraged because a pharmaceutical company has donated drugs for use for African natives that are beyond their expiration date, so he angrily dumps them all and castigates the company for making a meaningless donation just to get a tax donation. Maybe it’s the doctor who should be castigated because the expiration date on the drug has nothing to do with its efficacy. Here’s what Dr. Tedd Mitchell said in an April, 2005 article: It's important not to confuse a drug's expiration date with its shelf life. As long as you don't unseal the manufacturer's container, a drug may be good far beyond its expiration date. We know this because back in 1985 the Air Force wound up with a stockpile of medications that were just about to expire. Not wanting to throw away medicine (and money) unnecessarily, the Air Force asked the Food and Drug Administration to check the drugs for safety and effectiveness. The FDA estimated that 80% of the medications would remain safe for nearly three years past their expiration date. So the factual basis of this scene is blatantly false. Either the filmmakers were too lazy to get it right, or they were just taking a cheap shot, realizing that few people would have the knowledge that their premise was false. The problem is that its simplistic message influences anyone seeing the film who is not viewing it with a healthy skepticism to form a negative opinion the pharmaceutical industry for doing something that would be, in fact, a humanitarian act, donating valuable, but unsaleable, drugs to the needy. For a doctor to throw away urgently needed drugs for the sole reason that they are beyond a meaningless “expiration date” would be ignorant and reprehensible. But there’s a bigger problem with this scene for the movie. Everybody behind this film is on board with the message of the film that the pharmaceutical industry is evil. Maybe the main theme of the movie has some validity, that Big Pharma, as some like to call it, is corrupt, that it is only interested in profits, and that it conspires with big governments, like Kenya and Britain, to test its products on unsuspecting poor people. I don’t know whether that is valid or not. But I do know that the allegation of the film that drugs are worthless after the expiration date is hokum. If one of the film’s premises is hokum, how am I to trust the main premise? The movie would have been far more effective had it limited its issue to improper drug testing on innocently unknowing individuals. For the record, drug companies have developed amazing drugs that have contributed mightily to the quality of life. It costs hundreds of millions of dollars to develop these miracle drugs. Many of them turn out to be ineffective, which means all those millions of dollars are down the drain. The prices charged for drugs includes the cost of research and development of these drugs, many of which will never be able to be sold. The filmmakers claim that this is untrue and that most of the R & D costs come from government and charitable donations and grants. This is an interesting, entertaining movie which is worth seeing. My advice is to close your mind to the ill-informed message about the usefulness of expired drugs and watch with a healthy skepticism of the main premise. August 17, 2005 |

|

|

|

|