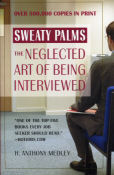

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

| Proof (10/10) by Tony Medley I’ve never seen a more moving, realistic account of a caregiver and the emotions that are peculiar to caregivers as Gwenyth Paltrow gives in Director John Madden’s conversion of David Auburn’s play, which won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the 2001 Tony Award for Best Play, Best Director (Daniel Sullivan) and Best Actress (Mary Louise Parker). Even though Paltrow has given some memorable performances, like “Sliding Doors” (1998) and including her Oscar-winning outing in “Shakespeare in Love” (1998), also directed by Madden, she has never been better. Unless something’s seriously wrong, always a distinct possibility in Hollywood, in my judgment this makes her a prime Oscar candidate. Throughout the film her eyes carry the weight of the burden, remorse, guilt, resentment, loneliness, and sense of loss that only one who has been a caregiver can really comprehend. Perhaps this is best captured when her father tells her on her 27th birthday that she should go out with friends instead of staying with him, and she replies, “In order for your friends to take you out you have to have friends.” Catherine (Paltrow) devotes some of the prime years of her life, ages 20-27, taking care of her schizophrenic father, Robert (Anthony Hopkins), a world renowned mathematician. Catherine worries that she will, or has, inherited his illness. He discourages this type of thinking, telling her, “Crazy people don’t sit around trying to figure out if they’re nuts.” His student, Hal (Jake Gyllenhaal), who is sweet on Catherine, following Catherine’s direction, finds a proof ostensibly written by Robert. But how could Robert have written it when he’s been the victim of a serious mental illness for seven years? The proof and the ensuing pursuit of the identity of its author is a metaphor for the lack of respect and credit caregivers are forced to endure and which adds to their psychological burden. Compounding things, Claire (Hope Davis), Catherine’s sister, shows up and plays on Catherine’s fears that she will inherit Robert’s illness and tries to run her life. Expressing emotions only a caregiver can appreciate, Catherine castigates her for ignoring her father and her for seven years and then showing up after his death and taking control, not only of the situation, but of Catherine’s life. This is an accurate reflection of real life because often the caregiver is the only one of two or more siblings who assumes the responsibility while the others ignore the elderly one needing care and fail to appreciate the sacrifice of the caregiver, and fail to express appreciation for assuming what should have been a shared burden. I was riveted by the brilliant dialogue of screenwriters Auburn and Rebecca Miller. Even though this is all talk, it’s talk that has more action than the most high flying action film, reminiscent of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” (1966). But it’s Paltrow’s eyes that convey what a caregiver feels. There are all the emotions mentioned above, but also an overwhelming sense of loneliness. The person to whom she has devoted her life and given all her love for seven years is gone out of her life, forever. It’s an incalculable feeling and loss and Paltrow expresses it throughout through the pain in her eyes, even if it’s never articulated. The characters are well-drawn and realistic. This is far removed from your feel-good Hollywood movie. Before it started I asked the running time, as I always do, and was told 1:50. At about the 1:35 mark, Hal tells Catherine, “We could sit down and track it through and determine if you couldn’t have.” I wrote the line down and noted, “If I were the director, this is where I’d end it.” And it ended! I like this director. This is a heavy, thought-provoking, involving film that left me exhausted, but invigorated; for my money one of the year’s best. September 6, 2005 |

|

|

|

|