|

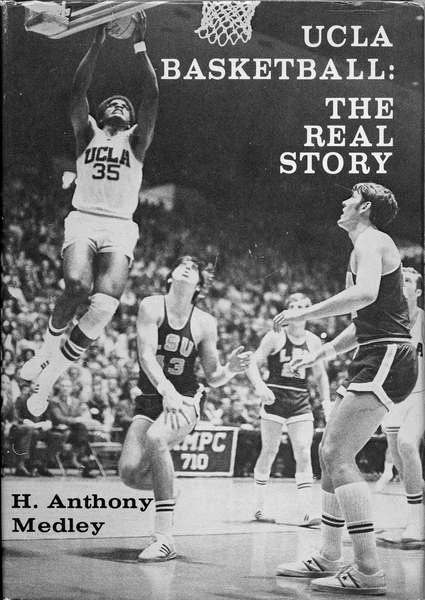

Out of print for more than 30 years, now available for the first time as an eBook, this is the controversial story of John Wooden's first 25 years and first 8 NCAA Championships as UCLA Head Basketball Coach. This is the only book that gives a true picture of the character of John Wooden and the influence of his assistant, Jerry Norman, whose contributions Wooden ignored and tried to bury. Compiled with more than 40 hours of interviews with Coach Wooden, learn about the man behind the coach. The players tell their their stories in their own words. Click the book to read the first chapter and for ordering information. Also available on Kindle. |

|

The Railway Man (8/10) by Tony Medley Runtime 108 minutes. Not for children. Screenwriter Frank Cottrell Boyce says, ďItís hard to make any film, but The Railway Man was particularly hard.Ē Hard as it might have been to write and produce, it is equally hard to watch. Almost half a century ago, David Lean made The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) based on Pierre Bouleís novel about the Japanese brutality in building railway (in fact there was no bridge and there was no river Kwai, and the film was shot in Ceylon). Although he showed Alec Guinness being tortured by being put in a metal cage in the sun, which drove him loony, the film doesnít begin to capture the dreadfulness and inhumane discomfort endured by the workers. Based on Eric Lomaxís book about what happened to him, Director Jonathan Teplizky filmed in Scotland and on part of the actual death railway in Thailand which was 258 miles long between Bangkok and Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myhanmar) reclaimed from the jungle. The line was closed in 1947 but the section between Nong Pla Duk and Nam Tok was reopened in 1957. About 180,000 Asian civilian laborers and 60,000 Allied prisoners of war worked on the railway. Of these, around 90,000 Asian civilian laborers and 12,399 Allied POWs died as a direct result of the project. The dead POWs included 6,318 British personnel, 2,815 Australians, 2,490 Dutch, about 356 Americans, and about 20 POWs from other British Commonwealth countries. Contrary to Leanís fictional, Hollywood approach (Lomax, commenting on Leanís film, said he had never seen such well-fed POWs), at first what happened to Lomax (Colin Firth) is left to our imagination. But Teplitzky shows the horror of the slave labor forced by the Japaneseís upon their POWs and other slave laborers in building the railway to be far worse than what Lean showed in 1957. The Japanese brutality and the heat and hopelessness of their labors are excruciatingly captured. But this is the true story of one man, Lomax, and how he survived the brutality and inhumanity of the Japanese and the post tramautic stress that followed the end of the war. Teplizky eventually shows what he was forced to endure, and it was heroic. This is a compelling tale of how Lomax faced his demons after the war with the help of the love and understanding of his wife, Patti (Nicole Kidman). In his book, however, Lomax barely mentions Patti. Teplizky realized that but for her, what happened in the film would probably never have occurred, so he gives her a much bigger part in the film than Lomax did in his book. Kidman gives a fine performance, but Firth is exceptional as the damaged Lomax. Iíve written before about how horrible the Japanese were to the people they conquered and how they have never apologized or tried to make amends. (see Japanese_and_the_Comfort_Women, and Rape_and_Japanese_Hypocrisy), so how Lomax dealt with his most vicious captor decades later is interesting and enormously powerful. While Lomax was involved in the making of the film to a certain extent, and while both Firth and Kidman dined with him near the end of the shoot, he died shortly before film wrapped, so never got to see it. |

|

|