|

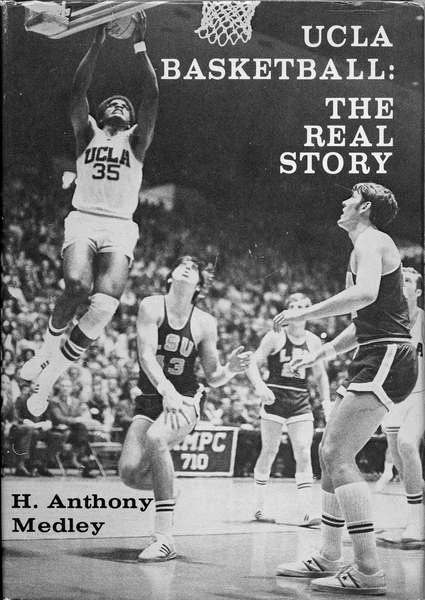

Out of print for more than 30 years, now available for the first time as an eBook, this is the controversial story of John Wooden's first 25 years and first 8 NCAA Championships as UCLA Head Basketball Coach. Notre Dame Coach Digger Phelps said, "I used this book as an inspiration for the biggest win of my career when we ended UCLA's all-time 88-game winning streak in 1974." Compiled with more than 40 hours of interviews with Coach Wooden, learn about the man behind the coach. Click the Book to read the players telling their stories in their own words. This is the book that UCLA Athletic Director J.D. Morgan tried to ban. Click the book to read the first chapter and for ordering information. |

|

A Walk to Beautiful (10/10) by Tony Medley Ask 10 men what fistula is and 9 will probably guess thatís itís a river in Poland. Ask 10 women and many, if not most, will probably correctly identify it. (To get technical, it is an abnormal duct or passage that connects an abscess, cavity, or hollow organ to the body surface or to another hollow organ). Obstetric fistula results from a prolonged pregnancy that causes a woman to be incontinent. Director (with Amy Bucher)-Cinematographer (with Tony Hardmon) Mary Olive Smith tells the stories of five Ethiopian women who suffer from devastating birthing injuries and who make the journey to reclaim their lost dignity. Although not many people here know about it, there are 2-3 million cases of obstetric fistula worldwide and 100,000 in Ethiopia alone. These cases are the most pathetic. Many are caused by young girls who are forced to marry at 13 years old and younger. When they become pregnant at such a young age, their pelvic area isnít big enough for a baby held to term to pass through. The result is an agonizing labor that can last as long as 10 days. Usually this causes the baby to be stillborn. The most dramatic aftermath of prolonged birthing is obstetric fistula, a hole that forms between the vagina and the bladder (and in some cases the rectum) during prolonged, obstructed labor. Affecting two million women worldwide according to conservative estimates, this horrific injury leaves victims incontinent, often suffering nerve damage, and in some cases unable to bear children. Because Ethiopian women live in a horribly impoverished country, they canít get medical treatment. Many live a six-hour or longer walk to the nearest road, making getting medical treatment extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible. So they are condemned to suffer with their problem. Abandoned by their husbands, their family doesnít want them around because they smell and are messy. So they are basically banished to live alone in shacks, feeling full of shame and rejection, just waiting to die. The title, ďA Walk to Beautiful,Ē reflects the difficult travel many fistula sufferers undertake to reach the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital. Most villages are a two-day walk from a road, and bus fares cost, what is for many, a fortune. Added to this is the misery and rejection of dripping urine, and sometimes feces. But without a cure, women with fistulas commonly spend the remaining years of their lives in shame and isolation. Smith tells the stories of five young women afflicted with fistula, Ayehu, 25, Yenenesh, approximately 17, Wubete, 17, Almaz, around 21, and Zewdie, 38, and a mother of 5 children when she became afflicted. She starts with them living alone and isolated from everyone else in their village and follows them as they learn of a possible cure, take the long walk, enter the hospital, and receive the treatment that could change their lives. Itís a journey Iím so glad I could watch them take. Each story is different and heart-rending. You wonít soon forget the sweetness of these women as each tells her heart-breaking story. Smithís film presents African natives in a light in which Americans probably donít often think; that they are people like us, with feelings as intense as ours. They donít live like us. They donít have beautiful clothes and nice houses and apartments in which to live. They donít have automobiles or television or electricity or roads or telephones or supermarkets or, even shoes. Worse, they donít have doctors and hospitals where they live in jungle villages. But in the end they are no different than we are with all our luxuries that we take for granted. These women have such tender, sensitive eyes, and express their suffering so eloquently, that you can feel the hurt every time you look at them, all the while admiring their bravery. Some of their comments are: ďI donít go visit my neighbors.Ē ďIím afraid someone will notice my shame.Ē ďMy husband wouldnít help me. He said itís my destiny to be like this.Ē The husband of the latter replied, ďI have needs so I moved in with someone else,Ē coldly and selfishly condemning her to a life of loneliness caused by a bad pregnancy in which he was a partner. These are just a few examples of how these poor, sweet women are abandoned when ill fortune hits them through no fault of their own. In fact, many are condemned to youthful marriages against their will which causes them to become pregnant before their bodies are ready for it. Each young woman tells her story in her own words. There is no narration. In fact, as the movie starts you donít realize what the problem is except for a few shots of the leg of one of the women, which clearly has fluid dripping down it. The World Health Organization has called fistula ďthe single most dramatic aftermath of neglected childbirthĒ. In addition to complete incontinence, a fistula victim may develop nerve damage to the lower extremities after a multi-day labor in a squatting position. Fistula victims also suffer profound psychological trauma resulting from their utter loss of status and dignity. Australian obstetrician-gynecologist, Drs. Catherine Hamlin, and her New Zealand born OB-GYN husband, Reginald, came to Ethiopia to spend a year. They were so taken by the good they could do for these poor, unfortunate, forgotten women, that they established their hospital, The Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital, in 1974. Its sole purpose is to treat women with fistula and related illnesses. Since then they have rescued 28,000 young women from the ignominious shame into which they had been cast, providing free fistula repair surgery to approximately 1,200 women every year and care for 35 long-term patients. You wonít see a more rewarding film this year. In Amharic & Oromiffa. February 3, 2008 |

|

|