|

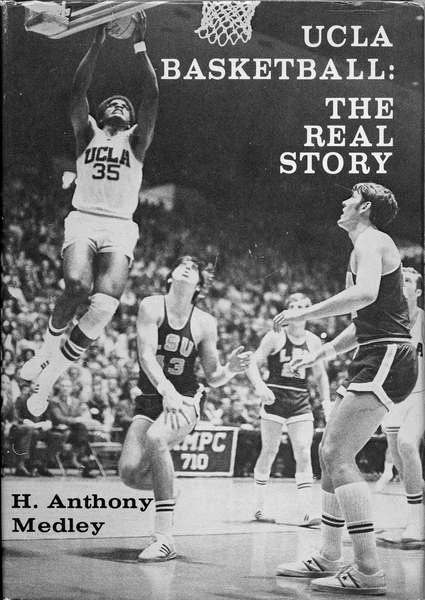

Out of print for more than 30 years, now available for the first time as an eBook, this is the controversial story of John Wooden's first 25 years and first 8 NCAA Championships as UCLA Head Basketball Coach. Notre Dame Coach Digger Phelps said, "I used this book as an inspiration for the biggest win of my career when we ended UCLA's all-time 88-game winning streak in 1974." Compiled with more than 40 hours of interviews with Coach Wooden, learn about the man behind the coach. Click the book to read the players telling their stories in their own words. This is the book that UCLA Athletic Director J.D. Morgan tried to ban. |

Show Business: The Road to Broadway (10/10) by Tony Medley Whenever I watch backstage stories about music, be it Broadway or recording an album or whatever, I’m impressed by the number of people who work on these things and the enthusiasm they all show. Thus it is that Dori Berinstein has made a quintessential documentary telling the story of four musicals as they prepare to open on Broadway, taking through their openings, up to The Tony Awards at the end of the year and then close with an epilogue 6 months after The Tonys. Berinstein shot more than 250 hours during the 2003-4 season, shooting on virtually every Main Stem attraction, then pared down in the editing room to tell in 102 minutes the backstage dramas of the four major musicals, from the low budget, $3.5 million Avenue Q, to the $7.5 million Caroline, or Change, the $10 million Taboo, and the $14 million blockbuster, Wicked. Along the way we learn many charming things about Broadway, like The Gypsy Robe Ceremony, which honors chorus members with the most credits on Broadway. The ceremony for each of the four shows is shown to the background of “Tradition” from Fiddler on the Roof. Players believe that the awarding of the Gypsy Robe helps to bless the show. Berinstein didn’t ignore the major Broadway critics. She arranged for four of them to get together four times during the year for lunch to discuss what was going on with the shows. They met at Orso’s, Angus’s, Joe Allen’s and Sardi’s. Those participating were Charles Isherwood of Variety, Michael Riedel of the New York Post, Jacques le Sourd of Gannet News/The Journal News, and Linda Winer of Newsday. This was a bad decision on Berinstein’s part, for two reasons. The first is that this is basically an honest documentary where Berinstein arguably had cameras in locations to film people as they worked. Nothing was staged. To the contrary, the critics’ luncheons are obviously staged. As such, they jeopardize the film’s verisimilitude, since, but for Berinstein these lunches, and their contrived, self-serving conversations, would not have taken place. Secondly, these people are so full of themselves, so unlikable, that the film loses its pace when it cuts to the meals. It did, however, capture the character of the critics, and it is not a pleasant sight. They sit around talking about “breaking boundaries” and “stasis is not something to show in a musical.” Who ever uses the word “stasis” in ordinary talk? Never once did I hear even one of them make any comment about whether or not the show is entertaining. Not once did they comment on the tunes or the lyrics. The dichotomy drawn between these people who express little but disdain for what they are seeing, and the love and devotion of the people who are putting on the shows is striking. Other critics interviewed during the film are Ben Brantley of The New York Times and John Lahr of The New Yorker. There are other fascinating facts. Jeff Marx, the youthful Composer and Lyricist on Avenue Q. revealed that he doesn’t read music. Since I can read music, and since it seems a simple skill, it thrills and amazes me that people can live their lives in music, like Paul McCartney, but can’t read it. Being able to create great music without being able to read it, for me, defines true genius. The Avenue Q story is one of the more compelling, created as it was by three young kids. Marx, an intern, and Bobby Lopez, a temp, wrote the words and music and Jeff Whitty the book. These were three guys out of nowhere. The people are so dedicated and in love with what what they do. The task is daunting; the decisions immense. When considering changes, George C. Wolfe, Director of Caroline, or Change, says, “To go from very good to brilliant is an endless series of details…unbelievable details that lift it.” It’s fascinating to watch the creative people actually creating. There is a terrific scene in which composer Jeanine Tesori is working on the epilogue for Caroline, or Change. She is clearly frustrated in trying to get it to work, explaining “This is the last big piece. It’s challenging. It’s important and it’s not really there. It’s really hard to do. Because you can muck it up very quickly if you rewrite the wrong thing because suddenly the house of cards comes in a big pile at your feet.” At one point she just bangs her head on the piano keyboard in frustration. Says Raúl Esparza, an actor in Taboo, “We’re all pouring all our energy and love into what we do…because that’s the reason we do it. You do it for a lot of love, I think.” The way these people sublimate their lives to their craft is impressive. Tonya Pinkins, the female lead in Caroline, or Change was divorced and lost her children a year before, but is bouncing back here. “There’s nothing you can do about that,” she says. Unfortunately, the song they show her singing is less than compelling. Berinstein had cameras at the locations where the people are watching the nominations for the Tonys. It’s clear that they take these awards very seriously, indeed, and that what we watch on the news when these nominations are announced, they are watching, too, hanging on every word. There is a touching telephone conversation between Lopez and his mother after he has learned he has received a nomination. The epilogue that brings the story up to date as of 6 months after the Tony Awards is highlighted by its music, mainly the Rogers & Hammerstein song from South Pacific, Cockeyed Optimist, in a unique arrangement by Jeanine Tesori performed by the Popstar Kids, and the Harry Warren/Al Dubin song for Gold Diggers of 1935, Lullaby of Broadway with another unique arrangement by Jan Follson and Tesori and performed by Idina Mentel, the star of Wicked with vocals by various people. If you love Broadway, you’ll love this movie.

|

|

|