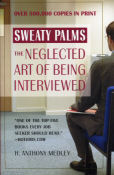

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. Click the book to order. Now also available on Kindle. | |

|

Book Review: “Shakespeare” by Another Name by Mark Anderson by Tony Medley I never bought into the theory that the plays attributed to William Shakespeare of Stratford upon Avon were written by someone else like Christopher Marlowe. My feeling was that genius appears haphazardly and it was just as possible that a great writer named William Shakespeare was born and raised in Stratford as it was that Michelangelo was born and reared in Caprese. Then an old friend of mine, John Devere, who was director of contracts at Litton industries Guidance and Control Systems Division where I was a Division Counsel, mentioned this book which is about a direct ancestor of his, Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, who was actually the writer of all of the plays attributed to Shakespeare. This is a fascinating book. It points out that there is no record that Will Shakespeare had any kind of education or traveled anywhere outside of the territory between Stratford and London. So how could he possibly have had the knowledge to write about many of the things and locales of his plays as accurately as they are portrayed in those plays? For instance, many of his plays are set in Italy in general and Venice in particular. There’s no record that Will Shakespeare ever visited any of those places. De Vere, on the other hand, spent a year living in Venice and traveling throughout Italy. Further, while there is no record of Shakespeare receiving any education or attending any kind of school in Stratford, de Vere received a classical education and spoke several languages including Italian and French. But there is more. Just as one of many, many examples of incidents in de Vere’s life that appear in Shakespeare’s plays of what Shakespeare would have no knowledge comes from Hamlet. Says Anderson: Visiting dignitaries to Mantua, such as an English Earl, would have been put up as a guest of the local Duke, Guglielmo Gonzaga. The Gonzagas had in 1575 (the year de Vere was in Italy) reigned as Dukes of Mantua for nearly 250 years. De Vere probably read tales from the family’s own bookshelves about the strange and curious history of the Gonzaga dynasty. One Gonzaga – a cousin to Castiglione – had been accused of murdering the Duke of Urbino by pouring poison in his ear. This is the same story Hamlet tells in his play–within–the–play, The Mousetrap. “His name’s Gonzago (sic),” Hamlet tells his colleagues at court. “The story is extant and rich in very choice Italian.” How would Will Shakespeare of Stratford who never in his life left England have been able to write something as specifically accurate as this? This is just one of dozens of examples of experiences from de Vere’s life that appear in Shakespeare’s plays that could not possibly have been in Will Shakespeare’s ken. De Vere wrote many plays that were performed for Queen Elizabeth and her court alone. Here is Anderson describing the essence of his book: … Most plays that were performed at Queen Elizabeth’s court are now supposedly lost. All that remains is a record in the Queen’s Royal payment books of the title of the play performed, the date and place where it was enacted, and the name of the troop that played it. Yet there may be more to a few of these records than first meets the eye. It is the contention of this book that De Vere wrote some of these “lost” courtly interludes. Then, during the 1590s and early 1600s he – probably with the assistance and input of others in his immediate circle of family, secretaries, and friends – rewrote these plays for the public stage. These revised texts constitute the central part of what is today called the Shakespeare canon. Much of Shakespeare is thus a palimpsest, popular dramas refashioned from works that were originally written for an elite audience in the 1570s and 80s. Anderson quotes many rumors that abounded at this time that there was a writer masquerading as having written someone else’s work. And he quotes from a letter Gabriel Harvey wrote to de Vere that includes the sentence, “Thine eyes flash fire, thy will shakes spears.” Anderson comments, “At the time Harvey uttered these words, a fourteen-year-old boy in Stratford-upon-Avon was still living in obscurity…It must be one of the great coincidences of Western literature that Harvey’s 1578 encomium to de Vere would reference the very name the earl of Oxford would one day use to conceal his own writings.” Anderson quotes a sonnet by contemporary dramatist and satirist Ben Johnson and then converts it into modern English for today’s reader: The man who many people think is England’s finest author (Will Shakespeare) is in fact a “poet-ape” – someone whose works are sloughed off pieces of wit from one or more actual authors. The “poet-ape” began his career as a play broker and then, emboldened, he became an out-and-out play-thief. We playwrights were mad, but we also pity the guy. He used to be sly and would cobble together bits and pieces of plays here and there. But now that he’s prominent in the London theatrical scene, he takes an entire play and claims it as his own. When he’s confronted with this he responds that others may figure out who wrote it–or not. But what a fool he is! With one’s eyes halfway closed anyone can easily tell the difference between hanks of wool and a whole fleece, or between mere patches and an entire blanket. Anderson also quotes Ben Johnson skewering Will Shakespeare (without naming him), in Every Man Out of His Humor: So enamored of the name of a gentleman that he will have it, though he buys it. He comes up every term to learn to take tobacco and see new emotions. He is in his kingdom when he can get himself into company where he may be well laughed at. Anderson even examines the only known portrait of Will Shakespeare, which had been dated at 1611, seven years after de Vere’s death, and presents evidence that it is actually a portrait of de Vere, painted by Dutch portrait painter Cornelius Ketel sometime between 1573–81, when he was in England painting royalty, and he did paint de Vere, but that painting had been lost. One piece of evidence is a statement made by Susan North, a textiles and dress curator, who said that the dress does not appear to date from 1611 and that the style “corresponds with men’s dress of the 1570s,” and that they went out of fashion in the 1580s. In summary, this is a fascinating book. It is a biography of the 17th Earl of Oxford and it makes reference after reference to specific incidents from de Vere’s life that appear in Shakespeare plays. While it is written based on the premise that de Vere wrote the plays, it convinced me. “Shakespeare by Another Name By Mark Anderson Gotham Books Published by Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Copyright by Mark Kendall Anderson First Printing April 2005 ISBN 1-592-40103-1

|

|

|

|

|