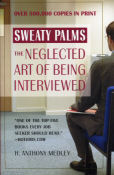

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

| The Express (5/10) by Tony Medley I think itís safe to say that you can count the number of film critics who actually saw Ernie Davis of Syracuse play football on the fingers of one hand, and have several fingers left over. If you tried that, I would be the first finger. On December 5, 1959, I was in the UCLA rooting section, one of 46,436 (the largest crowd to see Syracuse play that year except for the crowd at The Cotton Bowl against Texas), for the UCLA-Syracuse game played at the Los Angeles Coliseum. Syracuse routed Bill Barnesí Bruins 36-8. Davis was the highly touted sophomore halfback. Frankly, Syracuse was so overwhelmingly better than Coach Bill Barnesí under-talented and under-coached team that no single individual stood out on the Syracuse team, although guard Roger Davis was the player about whom I had heard the most; they all looked like Supermen to us. It was a rout from the first minute. Even though Davis was highly publicized as an outstanding sophomore, it wasnít one of his more memorable performances. In fact, in this film that game is mentioned only by a graphic that shows the final score and nothing more. Since this was Syracuseís last regularly scheduled game of the year, and gave them an undefeated season and an invitation to the Cotton Bowl, had Davis done much in the game, it would have been featured in the film. However, for his career Davis averaged 6.6 yards per carry, so his performance against UCLA was probably an anomaly. Although when considering this statistic, it should be considered that the two best running backs Iíve seen, and Iíve seen them all, were Gale Sayers and Barry Sanders, both of whom I only saw play in the pros. They played on horrible teams (the Chicago Bears and the Detroit Lions, respectively, and Sanders closed out his career with a coach, Bobby Cox, so stupid he constantly used Sanders, the best broken field runner in football, solely as a blocking back on pass plays). Every yard Sayers and Sanders made, they had to earn themselves because they didnít have any blocking. Davis, on the other hand, played on great teams at Syracuse (in 1959 they were 11-0; 1960 7-2; 1961 8-3), loaded with talent, so the majority of his yards were made because his line opened up huge holes for him. This film is a biography ďbased onĒ Ernieís life from about the age of 10 until his death at 23 of Leukemia, from a book, ďThe Elmira Express,Ē by Robert Gallagher, with a script by Charles Levitt. Directed by Gary Fleder, most of the film is devoted to the 1959 season when Davis was a sophomore and Syracuse was the top ranked team in the country. Unfortunately, Fleder has opted for the Hollywood version of football with audio that makes every hit sound like an atomic bomb explosion. Admits sound engineer Scott Martin Gershin, ďWe made choices during each game to use sound to enhance the conflict, whether it was playing the scene realistically or creating the hyper reality of a single breath as a player concentrates on the ball. This extended to a stampede of horses as the players raced to catch the runner, the sound of a locomotive smashing through the line of scrimmage, the sound of getting hit and having the wind knocked out of you...Ē Bad idea, because it converts a normal football game into something more violent than it really is, and actually detracts from the verisimilitude of the film. The Syracuse uniforms, especially the pants, didnít look authentic to me; even though they claim that they went to great lengths to reproduce what was actually used. I donít know what is was, but the players looked like they were not wearing hip pads in many of the scenes. Also, instead of using archival film of Davis (Rob Brown, who expertly captures Davisís good looks and good guy personality) in action, Fleder opts for extreme close-ups and quick cuts of action so you canít really appreciate Davisís running ability. Oh, sure, we see some cuts and some actors (most of whom were real football players) diving for him and missing and Davis dancing away for a long run, but itís all staged. Thereís no reason Fleder couldnít have used archival films to show some of his long plays and it would have added greatly to the enjoyment of the film. Or, how about putting them under the closing credits? Dennis Quaid gives a good performance as Syracuseís hard-driving coach, Ben Schwarzwalder, and Darrin Dewitt Henson plays legendary running back Jim Brown in a way that Brown will undoubtedly like, but which history might question. Fine performances are also contributed by Omar Benson Miller (who also shines in ďMiracle at St. AnnaĒ), who plays Davisís roommate, Jack Buckley, Charles S. Dutton as Davisís beloved grandfather, Willie ďPopsĒ Davis, and Saul Rubinek as Cleveland owner Art Modell. I attended law school at the University of Virginia with Betsey Evans Neely, who was a friend of Ernieís in high school and also at Syracuse, where she became Student Body President and she and Ernie were elected the two Marshalls of their graduating class. Hereís what she says about him, 45 years after his death: He was very intelligent, an economics major with good grades. He was very well respected for his intelligence, personality, social skills, charisma, the way he handled himself with everybody and the press, and a perfect gentlemen. He was a man worthy of admiration of young and old people alike. Our class is still emotional about him; we revered him. Hereís what high school classmate, and friend throughout the Syracuse days, Elmira attorney Jack Moore, says: Ernie was probably the best person Iíve ever met. He was everything youíre supposed to be; humble, caring about other people more than himself, great sense of humor, dressed well, respectful of teachers, a great human being. Our high school, the Elmira Free Academy, is now called Ernie Davis Middle School. The way you know if someone who starts talking about him knew him is if they start talking about him as an athlete, then they didnít know him because he was a better man. One problem with the film is that it concentrates on presenting racism that Davis allegedly faced, everywhere, but especially at Syracuse. When he arrives on the Syracuse campus on the first day, as he walks along he is subjected to hostile stares from all the white people who walk by. I asked both Betsey and Jack about this. They both were consistent in saying that not only were they unaware of any racism directed against him by fellow students at Syracuse, Davis never mentioned or complained about anything like this. In fact, Betsey was more specific, ďThe students at Syracuse had mostly been brought up in the north, in New York and places like that, and we had all attended integrated high schools. It would never occur to any of us to have any racist thoughts about a black person being on campus.Ē Moore also said something very compelling that acts as indictment of Fleder and Levitt that they had a racist agenda. He said that Davis wasnít the kind of a man to complain about anything like that to anyone. So, if Davis didnít complain about it, didnít talk about it with anyone, how could Fleder and Levitt come up with the scenes they inserted in the movie? Clearly, they must have made it up out of whole cloth to put a typical, Hollywood-approved racist agenda in the film. Lest you think this is preposterous, one of the games dealt with in the film is the 1959 game against West Virginia, which Fleder and Levitt set up as a racist attack on Davis and the entire Syracuse team by the West Virginia fans when they visit West Virginia for the game. They have Schwarzwalder tell the team before they take the field that he wants everyone to keep their helmets on the entire game, even when they are not playing, because he doesnít want them injured by things thrown by the racist West Virginia fans from the stands. Thereís only one problem with this scenario that takes up a fairly substantial part of the film; Syracuse played West Virginia in Syracuse in 1959, not in West Virginia; it was a Syracuse home game! Further exacerbating this dishonest theme of white racism, the film shows Davis as only hanging out with black people. If Neely and Moore are to be believed (and who are you going to believe, two people who grew up with him, loved him, and lived through these days with him, or two Hollywood types who never knew him?), this is far from the truth. According to them, everyone loved Davis and he couldnít possibly have only palled around with black people. Yet thatís what Fleder and Levitt would have viewers believe. Itís a shame that a film that should pay homage to a man who was clearly a wonderful person should rely on a phony, Hollywood-invented, story line of racism as a continuing theme. For a man who has been dead for almost a half century to still inspire the kind of emotion stated by Neely and Moore and those who knew him, he had to be an exceptional human being. Because this film chooses to concentrate on football, ignoring the things that Moore and Neely extolled about him, and because the filmmakers chose to create racism at Syracuse that did not exist, this movie is a disappointment. It could have been a wonderful monument to a man who was a lot more than a football player. Instead, in the words of Jack Moore, since it concentrates on Ernie Davis the football player, it doesnít know the man, and thatís the better story. October 8, 2008

|

|

|

|

|