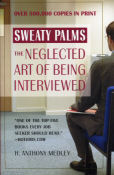

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

| Flash of Genius (8/10) by Tony Medley Unless you’ve actually been victimized by the American system of civil justice, you can’t know the pain and agony involved in litigation. This movie, good as it is, barely scratches the surface. Just as David Sarnoff of NBC stole the invention of television from Philo Farnsworth and put him through the legal mill worse than hell, Ford Motor Company appropriated Bob Kearns’ (Greg Kinnear) invention of the intermittent windshield wiper and basically destroyed Kearns’ life by stonewalling his claims. While this film shows what Kearns and his wife, Phyllis (Lauren Graham), and family went through, it doesn’t show exactly what really goes on. The film implies that the worst part of it was just the failure of Ford to give Kearns credit. But that’s not the worst part of litigation. It shows the perfidy of his attorney, Gregory Lawson (Alan Alda), but it does not show the hell of Discovery, the myriad of motions, the depositions, and the other ordeals of American style civil litigation. It doesn’t even begin to show the lazy, biased judges with whom one is faced when forced to litigate. This film punts on attacking the judiciary, showing the judge (Bill Smitrovitch) as a benign, fair, competent arbiter, something that is as rare as a hen’s tooth in American courts. Based on a true story, Kearns slowly finds that he is alone in this horrible world in which he finds himself trapped, unable to count even on his longtime friend and partner, Gil Previck (Dermot Mulroney). In the end, if one is paying attention, it is difficult to determine who actually won the case. But to say it is “based on a true story” means that there is a lot that is left out, and it’s what is left out that makes the film much weaker. What would be meaningful for American moviegoers is to see a film that shows the horrors of civil litigation in detail. This film barely alludes to the agony of Discovery. Greg Kinnear, who has come off two disappointing performances in two dismal movies (“Ghost Town” and “Baby Mama”), shines in a difficult role. Laura Graham gives a quality performance as Kearns’ long-suffering, supportive wife, who was at least as much a victim as Kearns, although she’d get my vote as the biggest victim of them all. Alda is very good as Kearns’ slimy attorney (but I repeat myself), starting out like gangbusters and then acting like the worst TV huckster pressuring Kearns to take Ford’s meager settlement offer. I would have been much more enthusiastic about this film if it had emphasized the moral corruption of the American system of civil justice than just heaping all of the blame on Ford. Ford, so be sure, acted atrociously, but all Ford did was to recognize the main pitfall of American civil courts, that they grossly favor those with deep pockets. Ford knew this, as do all major corporations, and they used it to their advantage. What’s right and honorable had no place in Ford’s world; what’s best for the shareholders is their only standard. It was just Ford’s misfortune to be matched against an honest man to whom his personal reputation was more important than money and family. Frankly, I don’t think that Kearns comes out of this movie as much more admirable than Ford.

September 24, 2008

|

|

|

|

|