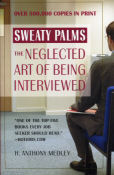

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

|

Glory Road (1/10) by Tony Medley Don’t demean this picture. This isn’t just one of the worst sports movies of all time; it can hold its own with the worst of any genre. I don’t have a lot of time and space, so let’s cut to the chase. This is a movie without a premise. Producer Jerry Bruckheimer and director James Gartner would have everyone believe that the game that is the subject of this film, the 1966 NCAA Championship Game between all-white Kentucky and all-black Texas Western, was “the game that changed everything.” I guess because it was the first NCAA championship game in which all five starters were black. I guess that was supposed to, somehow, have changed the world. Well, it sounds good if you don’t know anything about basketball history. But Jerry and James should explain why this team was much different from the Cincinnati team that won two consecutive NCAA titles in 1961 and 1962. The 1961 team had three black starters, Paul Hogue, Tom Thacker, and Tony Yates. The 1962 team had four black starters, with George Wilson joining Hogue, Thacker, and Yates. Thacker, Wilson, and Yates returned the next year only to lose in the Championship game to Loyola of Chicago in overtime. As I recall, Loyola’s starting team contained a majority of black players, too. So to try to say that the Texas Western team “changed everything” ignores history. Black-dominated teams were nothing unusual by 1966. There are those who feel that starting five blacks was ground-breaking. The movie should explain the difference between starting four and starting five, and why the latter was so much more important than the former. But, even if it did, without a premise, a movie is a lifeless, glob of flotsam. This one doesn’t even rise to that level. The movie is made from the book by the coach, Don Haskins (Josh Lucas). I didn’t read the book, but if the movie is at all faithful to its source, it is undoubtedly self-serving. Haskins lives in the infamy of my memory because he was U.S. Olympic Head basketball coach Hank Iba’s assistant coach of the 1972 Olympic team, the first U.S. team ever to lose an Olympic basketball game. That was the infamous game when the Soviets were given three tries at the last three seconds and finally won it with a full court pass. But Iba and Haskins should bear full responsibility for the loss. In the first place, give me the best American college players and you can have 100 tries at going full court in three seconds to score and you won’t succeed. But Iba and Haskins should never have been in that situation. Had they devised the proper strategy and played the Soviets straight up, they should have won by 20 points. Iba and Haskins were so clueless that they coached the team in their slow down, control the ball style, even though Olympics basketball plays with a 30-second clock and when you have such overwhelming talent, the last thing you want to do is slow the tempo. But that’s exactly what Iba and Haskins did, and the result was the first U.S. loss ever and no Gold Medal. Maybe Haskins’ next book will be to rewrite history on that game, too, since he’s been so successful in sucking in a big time Hollywood producer to put his spin on this game. If you want to know the truth, the 1966 NCAA Championship game pitted against one another two of the weakest teams ever to play for the title. Kentucky’s two best players were Pat Riley and Louie Dampier. Riley, at 6-4, jumped center, but wasn’t a strong enough player to do much more in the NBA than be 10th and last man on the Lakers team that set the record of 33 consecutive wins. Dampier was better, but spent most of his pro career in the ABA. Texas Western really only had one player of quality, center David Lattin (Schin A.S. Kerr), and he was only good enough to have a sip of coffee in the NBA, playing two years for a total salary of around $40,000. The movie demeans the sacrifice required of Haskins’ wife, Mary (Emily Deschanel) but then the movie is about him, isn’t it? She was forced to live in a dorm with her two children while Haskins coached the team. Her burden is barely mentioned in the film. Apparently, she was asked to endure a monotonous, lonely life. But Bruckheimer is too macho to pay any attention to that. The movie shows Haskins going to New York to recruit three playground players, Willie Cager (Damaine Radcliffe), Nevil Shed (Al Shearer), and Willie Worsley (Sam Jones III) from New York City. I guess we are supposed to buy the idea that these guys were three gems whom Haskins purloined off the streets of New York because nobody knew about all the playground players in the north. But that’s simply not so. Everyone knew about the playground players in the north. All-Americans Walt Hazzard (UCLA) and Wayne Hightower (Kansas) and Wally Jones (Temple), just to name three, were all recruited off the playgrounds of Philly. What might be true is that the players Haskins recruited for Texas Western were available because they didn't have the academic background to get into any University with academic standards and that Texas Western was willing to turn a blind eye to academic qualifications. And I do have facts for at least one of the players. UCLA sent an expression of interest to the high school coach of David Lattin in Houston. Lattin turned out to be Haskins’ best player. Included in the letter was a request for a transcript showing what kind of student Lattin was. No response was received, but several months later Lattin’s coach telephoned UCLA and said he and David were at the airport with a five hour layover. David, he said, was very interested in UCLA and would like to take a tour of the campus. He was told that in the letter a transcript had been requested and that Lattin would have to be academically eligible or he would not be admitted. Long, long pause. Finally, Lattin’s coach said, “Co-ach,” (two syllables), “after you see him play, you’ll find a way to get him in.” That was the end of Lattin at UCLA because there was no way. But at Texas Western, apparently, there were no educational requirements and that’s probably why all these guys from New York City and Detroit (Bobby Joe Hill, played by Derek Luke), and Gary, Indiana (Harry Flournoy, played by Mehcad Brooks, and Osten Artis, played by Alphonso McAuley), ended up in El Paso, of all places. Like Lattin’s co-ach, Bruckheimer and Gartner keep all mention of academics and grades and going to classes and getting an education out of their movie. And this raises an essential issue implied, but not said, in this movie. An important point that should have been dealt with is the issue of granting admission to a University to athletes who are academically unqualified for the sole purpose of playing sports. At the end of the movie we are told what happened to each of the major players. Not one word is mentioned about whether or not any of them graduated from Texas Western. If this is true, that none of them graduated, a conclusion may be drawn that these young men were unqualified to attend university. As such, they took the place of legitimate students who were qualified. In addition, they took the place of qualified student-athletes who had to sit on the bench while they played. Did they get an education? Did attendance at Texas Western help them in subsequent life? The movie is silent on these matters. All it talks about is winning on the court. Is success on the basketball court justification for this? Even worse than the weak script (Christopher Cleveland and Bettina Gilois) is the cinematography by John Toon. Basketball is a beautiful sport to watch. It can be made almost balletic when shot by talented photographers. Unfortunately, Toon apparently does not fit into that mold because the basketball shots look like something you’d see in a basketball movie made in the 1950s, if there were such a creature. Quick cuts, mostly slam dunks, nothing visually memorable, although Bobby Joe Hill's steal in the opening minutes of the game is admirably comparable to what actually happened in the real game. It’s hard to believe that a sportscaster could be more inept than those who grace the real airways, but listening to how Cleveland and Gilois have their sportscasters call the games of Texas Western makes one long for the meaningless gibberish of the “Oh, My” guy from real TV. One time they throw in that someone scored on a “back door.” The only problem was that the play on the screen that he was describing wasn’t a back door. But it sounded good if you weren’t watching that closely or, more probably, wouldn't know a back door from a turnip. I’m already way over my word limit. If you’re not a basketball fan, this film is boring, manipulative, and banal. If you are a basketball fan, it’s worse. |

|

|

|

|