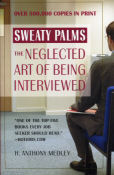

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

| Friends with Money (5/10) by Tony Medley Men need not apply. While this may seem horribly politically incorrect, if there has ever been a chick flick in the worst sense of the word, this is it. The women are smart and articulate. The men are either dysfunctional, insensitive boors or gay, with one exception. The only way a man should find himself inside a theater showing this movie is if he is either trying to elude the police or erroneously thought from the title that the film was about Gordon Gekko. Let me be clear, however; there’s nothing wrong with films about women. I can think of two that I enjoyed immensely, George Cukor’s “Rich and Famous” (1981) with Jacqueline Bisset and Candice Bergin, and “The Turning Point” (1977) with Anne Bancroft and Shirley McLaine. It’s films about women that are clearly misandristic that give the genre a bad name. This perpetuates many of the hoariest myths that feminists constantly assert, to wit:

They are all hogwash, but they are all in this movie. Christine (Catherine Keener), Jane (Frances McDormand), and Franny (Joan Cusack) are the middle-aged, wealthy married ladies who are somehow great good friends with Olivia (Jennifer Aniston), who is much younger, single and apparently unable to get a date, or at least a date who knows something about commitment. Poor Olivia has quit her job as a teacher and is working as a maid for $65.00 a day. It is never explained how these three jaded women include in their clique the young Olivia, who still has her life to live before her. Or why the youthful, beautiful Olivia would voluntarily imprison herself with three bitter nags. This is not just a movie about women, it is also about their marriages. The one thing that all the marriages shown here have in common is that none displays one iota of affection between spouses. I don’t remember a hug or a kiss or even many kind words. What is the purpose of these marriages? Was there ever any love? Was there ever any reason to get married other than money? If so, what happened? The movie is silent on these issues. Why did they ever get together? All three seem little more than poorly-matched roommates. But the idea one gets is that this is an accurate depiction of the state of matrimony in upper middle class modern day Los Angeles. Not a pretty picture. The dialogue is interesting, but it presents a slanted, negative, one-sided look at its subject. These people are so unsympathetic with one another if marriages were really like this, there would be no raison d’être. The lack of even-handedness in this diatribe by writer/director Nicole Holofcener is surprisingly disappointing after the terrific job she did with her last film, “Lovely and Amazing” in 2002. To give Holofcener the benefit of the doubt, it’s possible that she is not cutting a wide swath here, indicting all marriages of upper middle class people in Los Angeles and saying they are all alike. “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” (1966) was a brilliant study of a dysfunctional marriage that didn’t intend to say that all marriages of academics were similar. So maybe Holofcener is just giving us a picture of three isolated marriages and not drawing any wider conclusion. That’s possible, but that’s not the way I walked away from this film believing. Consistent with my opinion on Holofcener’s intent is the resolution of the story, which strongly implies that a man is only worth as much as his net asset value. Forget kindness, compatibility, love, and affection, if he’s got a bank account, he’s worth nabbing. March 15, 2006

|

|

|

|

|